Leadership Eats Strategy For Breakfast.

Over the last ten years, Consulting Within Reach (CWR) has successfully completed over 250 projects for nonprofits. These projects delivered strategies in overall organizational direction, programming, marketing, and fundraising. We have served numerous nonprofits widely recognized to be critical to the social well-being of the Bay Area.

If asked to summarize in just two words the most important insight earned from our body of work, we would say this: Leadership wins.

Mediocre strategies in the hands of excellent leadership will beat out excellent strategies in the hands of mediocre leadership. Every time. In particular, the leadership talent at the very top of nonprofit organizations wins over all. Therefore, any funder who cares about the long term future resilience of nonprofits – and the communities that depend on them – should care about the flow of future nonprofit executive directors.

But this talent flow is desperately weak. Numerous sector-wide studies describe this weakness with findings such as:

• Nonprofit leadership teams “single out leadership development and succession planning as their most glaring organizational weakness by a margin of better than two to one” (Bridgespan’s national survey of nearly 900 leaders).

• Only 17% of organizations have a documented succession plan and only 33% of executives believe their boards will succeed in hiring their successors (CompassPoint’s survey of over 3,000 executive directors).

• The nonprofit sector devotes a mere .03 % of annual spending on leadership development at all levels. Per-person spending on leadership development among nonprofits is less than a quarter of what the private sector spends (a national study conducted by the Foundation Center).

• Multiple studies warn of an impending shortage of homegrown executive directors and that “the sector is potentially facing the simultaneous burnout of younger leaders and the retirement of Baby Boomers” (Open Impact’s recent report).

Based on our local experience, the state of Silicon Valley’s nonprofit talent development is probably even more threatened than the national average. An informal scan of our client base of local organizations suggests that less than 5% of them possess a systematic approach to leadership development. Even fewer have a plausible succession plan in place. Our clients report that the high cost of housing in the South Bay and high salaries offered by the private sector make talent recruitment and retention especially difficult. One prominent recruiter reported that San Jose nonprofits especially suffer because the city loses out to San Francisco or Oakland in terms of cultural appeal.

The Flawed Model

The commonly cited reason for the weakness of nonprofit executive talent development and succession planning is the lack of financial resources devoted to the issue. But when we imagine a scenario where every one of our clients suddenly received a few thousand dollars a year for executive talent development – but nothing else changed – we believe that the overall improvement achieved in our sector would still be marginal.

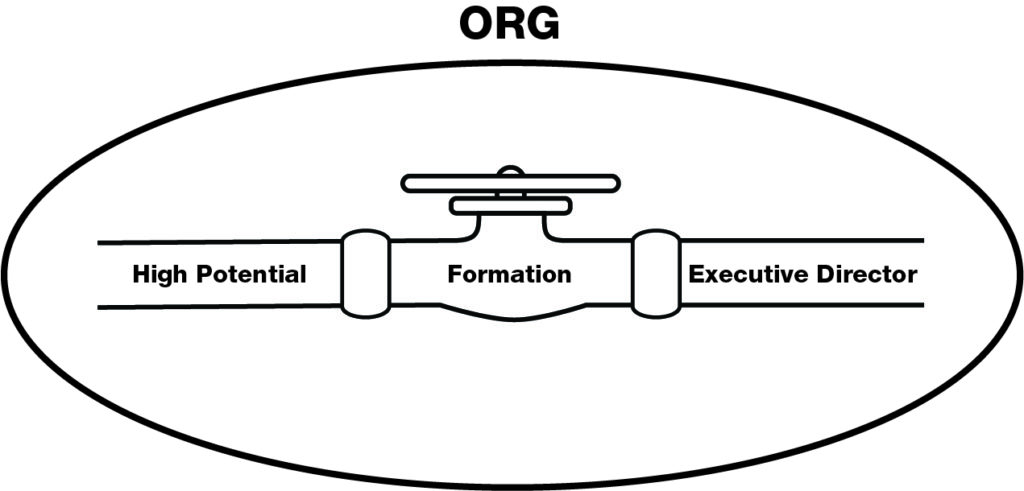

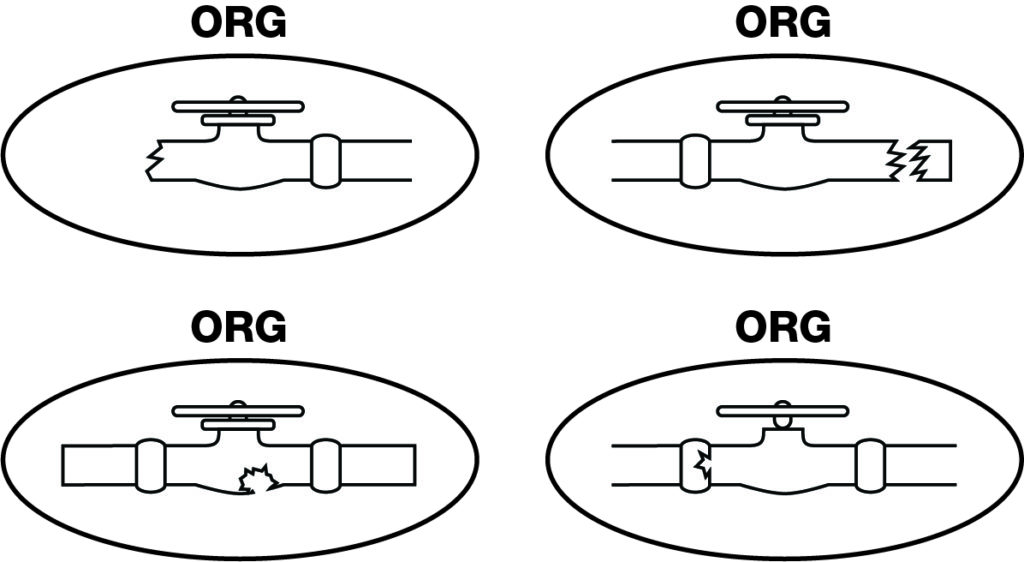

The reason: the prevailing model for nonprofit talent development and succession planning is fundamentally flawed. The flaw is the requirement that each organization must construct its own executive talent pipeline within itself and isolated from others. The overwhelming majority of nonprofits are simply unable to succeed with this model.

Consider how constricted the High Potentials end of this pipeline is within most nonprofits. The overall number of individuals with the raw ingredients to become a successful executive director in the future is already small. The small numbers that do exist are not evenly distributed across all organizations at all times. At any given moment, many (probably most) local nonprofits simply do not have anyone in their ranks who plausibly could ever become a future executive director. Further straining plausibility is the additional expectation that every organization must have such a High Potential on a developmental timeline neatly synchronized with the likely departure timeline of the current executive director.

Even if every nonprofit somehow magically did possess one person with executive director potential, that number is still too small for optimal development. Individuals grow best when connected with others of similar talent and drive. But the current model isolates High Potentials from their peers in other organizations. Existing networking structures in our sector are heavily skewed towards convening executive directors, not middle management where most High Potentials reside. Currently, innovations in talent development and social capital formation – like the Haas Flexible Leadership Awards – gravitate towards existing executive directors.

The rare programs that do connect High Potentials residing in the middle ranks of organizations share a common tendency: they either narrowly target a mission field and/or cultivate national social capital. Innovative programs like the Knight Foundation’s own Emerging City Champions or OneJustice’s Executive Fellowship (for legal aid executives) provide a great deal of benefit, but they do not build and connect the overall High Potential talent base in a local context. The few models of local leadership development in the Bay Area that can include “middles” – such as Leadership San Jose – do not focus on developing nonprofit executive directors.

The current model also suffers from the constricted nature of the opposite end of the pipeline – that of current executive directors. In a sector where organizations are considered “advanced” if they have even just one person dedicated to HR, the prevailing model relies on the executive director to carry the primary burden of high level leadership development. But the demands on an existing executive director are myriad and unrelenting. An executive director’s bandwidth to coach, mentor, and train is always getting squeezed. Moreover, not all executive directors have the ability to develop their successors. Leading and developing future leaders are not the same thing: the latter requires a specific temperament and expertise.

Finally, consider the constricted nature of the formation process itself. Many nonprofits are too small to construct and maintain any formal leadership development process by themselves. And practically all nonprofits will struggle to provide the specific kind of development most needed for future executive directors. Getting practice in building external social capital is critical for any future executive director. The art of relating with individual donors, foundations, government, and partner agencies is what most differentiates the executive director from her staff.

But in the current model, a nonprofit will struggle to provide its High Potentials with meaningful opportunities to build these types of external social capital. Executive directors in our network often describe bringing a staff member to some externally facing meeting, only to have audiences nevertheless focus all attention on the ED as the true voice of the organization.

Our sector needs a new model of executive talent development and succession planning, one that does not mean hundreds of weak or non-existent pipelines isolated within nonprofits.